Researchers say taking a peek inside a person’s brain is as difficult as understanding the universe or discovering the ocean in its entirety.

Nevertheless, they march on, all in the name of science.

“The brain is a fascinating organ,” says Dr. Viviane Poupon, president and CEO of Brain Canada. “I don’t think we [do enough to explain] to the public the complexity of how it functions. It has many connections between the neurons and the different cells that we have.”

Brain Canada is a nonprofit organization created in 1998, then called the NeuroScience Canada Partnership and Foundation.

“Our focus is in supporting research on the brain, understanding better how the brain functions in health and in disease, and really support the entire Canadian ecosystem,” said Poupon. “It’s really, really important that we make breakthrough discoveries about our brain. So, this is really our key mission.”

She says the goal is simple: allow Canadians to live life with as healthy a brain as possible for as long as possible.

“You also like to try to look at commonalities because it can be the same mechanism that leads to different neurodegenerative diseases,” she said. “You need to understand these drivers because they can have implications in one disease or another.”

An important part of the science, Poupon explains, is understanding how the brain interacts with the rest of the world.

“That’s where we support all sorts of research about the brain. We have a holistic approach about the brain. We see it as a whole,” she said. “It’s not just what happens between our ears in isolation; our brain reacts to our internal environment and external environment all the time.”

Poupon notes that research includes everything from how cells interact to how memory forms and how these mechanisms can break down over time.

“Why [does] a normal, healthy brain all of a sudden get into a different trajectory and start developing a disease?” she asks.

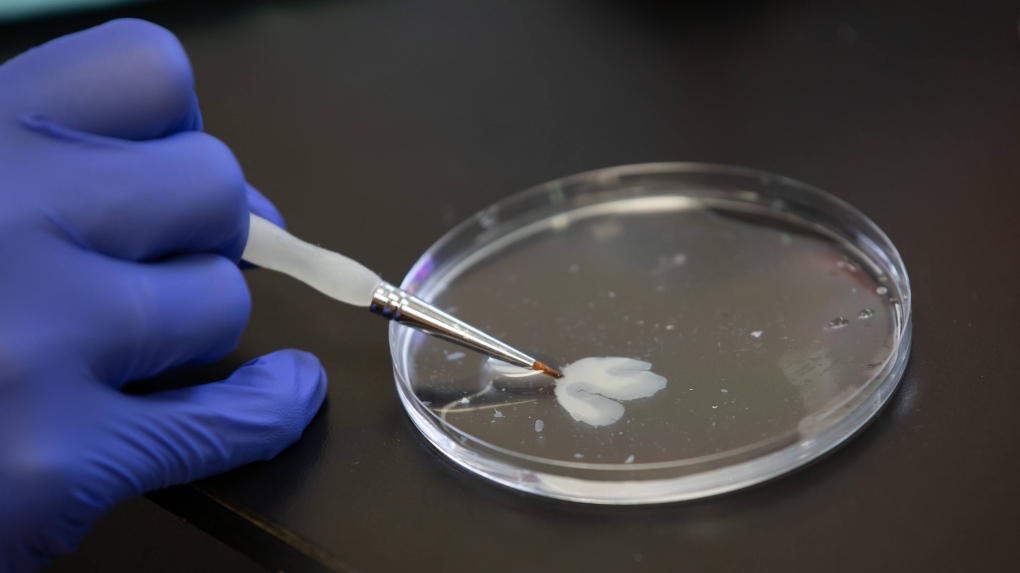

One of Brain Canada’s main collaborators is the brain bank at the Douglas Research Centre in Montreal.

It is a collection of 4,000 brains donated by individuals, many of whom lived with various neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, dementia and ALS.

“The brain remains an organ of our body that is not well known,” explains Dr. Gustavo Turecki, scientific director at the Douglas Research Centre. “We still understand very little about how the brain works: where in the brain certain processes are regulated; how our emotions, our behaviours are regulated; and what happens when things don’t work well.”

The bank also analyzes the brains of people diagnosed with mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder, and more.

The brain bank at the Douglas Research Centre. (Owen Egan)

One of the main challenges of studying the brain?

“The only way to really understand is by having access to brain tissue. Unfortunately, you cannot sample brain tissue from living subjects,” Turecki said.

He notes that age, sex, ethnicity and even the environment can affect people’s brains differently.

“Different labs and different investigators that ask different questions have found different things,” he explains. “There are so many things that have been impossible to find until now…without the brain tissue that we have in the bank, it would have been impossible.”

He admits that getting consent to analyze a person’s brain is a “delicate” issue.

“We need the consent immediately following death because the brain needs to be collected within 24, 48 hours max,” he said. “Even though they are going through a very difficult experience, [they’re] donating the brain that can help other families avoid the outcome that they are going through…We help understand why somebody died.”

Poupon adds Brain Canada’s hope is that the research will eventually lead to better diagnostics and pinpointing of biomarkers to create more promising treatments for people living on the spectrum of brain disorders.

“This is a collective wealth that’s available for researchers in Canada and across the globe to answer questions about what I’m discovering; what I’m looking at in my lab, in a cell, or in an animal model: is it actually what’s happened in a human being?” she said.

Looking to the future, Poupon says she’s “really looking forward” to seeing what researchers discover in the next decade.

“I think there’s a lot of promise in brain health research. There is no innovation, there is no drug, there is no treatment that didn’t start in the lab through research,” she notes. “When you do research on the brain, it’s like the man trying to understand his own complexity and his own way of thinking and how we approach the world.”